[ see cards ]

Sakaeya Shoten (also Sakaeya) was founded in May 1893 (Meiji 26) by Kotaro Imaki, born in Toyoura-gun in Yamaguchi Prefecture, as a shop selling ryumon stamps (see right). It was located on Motomachi-douri 3 chome in Kobe, Hyogo Prefecture.1

Sakaeya Shoten (also Sakaeya) was founded in May 1893 (Meiji 26) by Kotaro Imaki, born in Toyoura-gun in Yamaguchi Prefecture, as a shop selling ryumon stamps (see right). It was located on Motomachi-douri 3 chome in Kobe, Hyogo Prefecture.1

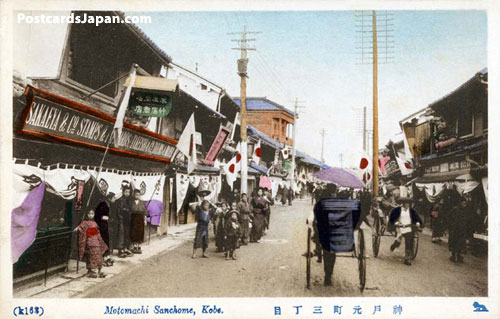

Ryumon stamps were extremely popular with foreign collectors and exported worldwide. Sakaeya was therefore perfectly located on Motomachi-douri, which was Kobe’s main street at the time and within short walking distance of the foreign settlement. Foreigners were actually allowed to live in Motomachi, making it one of the few places in Japan where both foreigners and Japanese lived in the same area.

Besides stamps, the company also sold imported playing cards, imported framed paintings and other imported goods.1 This later turned out to be pivotal to Sakaeya becoming a publisher of postcards.

First cards

Sakaeya first started selling postcards some time after the closing of the Sino-Japanese War in 1894-95 (Meiji 27-28),1 probably in the late 1890s (early Meiji 30s).2 This makes it, together with Yokohama based Ueda (also Uyeda), one of the first postcard publishers (ehagakiya) in Japan. Remember, this was at a time when the word ehagaki (picture postcard) didn’t even exist yet.

It appears that the postcard business was not very profitable and soon sales were stopped. Sakaeya was many years ahead of its time.

The time was finally ripe for postcards when the Russo-Japanese War broke out in 1904 (Meiji 37). The war created an enormous postcard boom in Japan, which lasted from 1904 (Meiji 37) through at least 1907 (Meiji 40). In 1890, 96,430,610 postcards were sold in Japan, by 1913 this had risen to 1,504,860,312. Only in Germany more postcards were sold.4

By sheer coincidence, at around the start of the conflict some 200 postcards of flowers were mixed in with a foreign shipment that arrived at Sakaeya. Imaki had not ordered them, but decided to put them out in his store anyway. They sold as hot cakes. Good businessman that he was, Imaki immediately realized the opportunity and decided to go into the postcard business. Sakaeya became both a publisher and wholesaler of postcards.1

The Sakaeya store on Motomachi in Kobe, c. mid 1900s

Success

The company was clearly good at what it did. During a 1906 (Meiji 39) postcard exhibition in nearby Osaka organized by Osaka Minatsukikai, the company won an award for a series of 8 postcards entitled “Kobe yori Akashi,” showing the area between Kobe and Akashi as it appeared 200 years earlier.1

The success of the postcard business inspired Imaki to begin producing postcard and photo albums. He also appears to have sold a large number of photographs of famous Japanese movie actors and actresses.1 These kind of photos are called bromides in Japan, not to be confused with the bromide photo process.

Imaki’s success was not limited to his business. He and his wife were the proud parents of ten children, seven sons and three daughters. Each of them seems to have inherited their father’s acumen. One son for example studied at Tokyo’s famous Waseda University, while another started working with the highly respected Daimaru Department Store chain.13 Imaki’s ability to give his children a good education is proof of the enormous financial success he must have enjoyed.

This success however, did not seem to go to his head. He was known as a quiet man who said little and enjoyed reading.1

In the 1940’s, Sakaeya sold mainly bromides and imon hagaki, ‘sympathy cards’ that girls sent to soldiers at the front.3

The Second World War spelled the end of Sakaeya’s postcard business. The shop was burnt to the ground in 1945 (Showa 20) during a firebombing air-raid by US planes. After the end of the war, the family did not return to the postcard business.3

About Sakaeya’s cards3

Marked Sakaeya cards are easy to recognize because of the distinctive Lion Mark on the lower right corner on the front of the card (see card above). It begins to appear around 1911 (Meiji 44). By this time the shop was famous and Sakaeya’s name had become representative for Kobe postcards. It sold many cards with images of buildings and locations in Kobe and surroundings, which now repeatedly show up on auctions and postcard fairs.

Hand-tinted Sakaeya cards are usually numbered with a letter preceding the number, both enclosed in parentheses: (k111). They have no Sakaeya markings on the back.

There are also cards with the lion mark where the letter-number code is not enclosed in parentheses: k111. These cards usually have an Ueda back (see Ueda mark right). Ueda appears to have published a very large number of Kobe cards, usually without the lion mark.

There are also cards with the lion mark where the letter-number code is not enclosed in parentheses: k111. These cards usually have an Ueda back (see Ueda mark right). Ueda appears to have published a very large number of Kobe cards, usually without the lion mark.

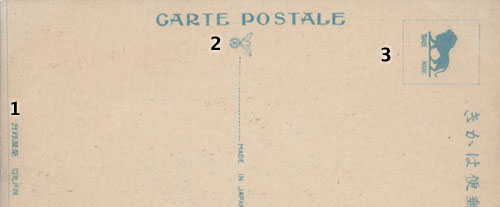

Later cards with the lion mark are black and white. The mark is not on the front, but on the spot for the postage stamp (3). The Sakaeya name is printed on the far left edge (1). Often a dove mark of Wakayama based postcard publisher Taisho (Hatto) is printed above the dividing line (2).

Part of the back of a later Sakaeya card

Sakaeya was not the only Kobe based publisher of postcards, Another postcard publisher in Kobe was T. Takagi. This company printed its name on the back of the card, making it easy to distinguish the company’s cards from Sakaeya cards.

Acknowledgements:

This article was written together with Yujiro Yasui

Ryumon stamp icon courtesy of Meijitaisho.net

Footnotes:

1 “Kaiga ehagaki ruihin fuzokuhin bijitsu insatsu seihin shi ire taikan,” published in 1925 (Taisho 14) by Dainihon Ehagaki Gepposha, Osaka.

2 The production and sale of postcards to which a stamp could be affixed was officially authorized by the Japanese government in October 1900 (Meiji 33).

3 Original research and interviews.

4 Propaganda on the Picture Postcard, John Fraser, Oxford Art Journal, Vol. 3, No. 2, Propaganda (Oct., 1980), pp. 39-47

Recent Comments

I have seen a bottle at its label is clifford wilkinson TANSAN

i have a bottle color green,and it has a clifford wilkinson written on the bottle..

Hi I have a copy of this postcard sent to my mother by my father dated 10 sept 1945 while he was in Japan in …